4 The Great Fire of 1901

How Government Response Raised Jacksonville from the Ashes

Carson Welch

“It is not necessary for me to say that our city has met with as great a disaster as has ever fallen upon an American city, nothing but a barren waste remains… but there is immediate relief necessary, and for this purpose action must be taken at once.”1

C. E. Garner, president of Jacksonville’s Board of Trade

As the people of Jacksonville, Florida woke up to the final workday of the week on Friday, May 3, 1901, they were unaware of the fact that most of downtown Jacksonville would burn to the ground before the day ended. While the speed of the fire and its consequences for the people of Jacksonville were remarkable, the recovery and relief efforts in the days after the fire were equally swift and consequential. The Governor of Florida, the Mayor of Jacksonville, the Jacksonville City Council, and other city boards and committees took immediate, decisive action in response to the Great Fire of 1901, which demonstrated the resilience and focus of Jacksonville’s people and institutions.

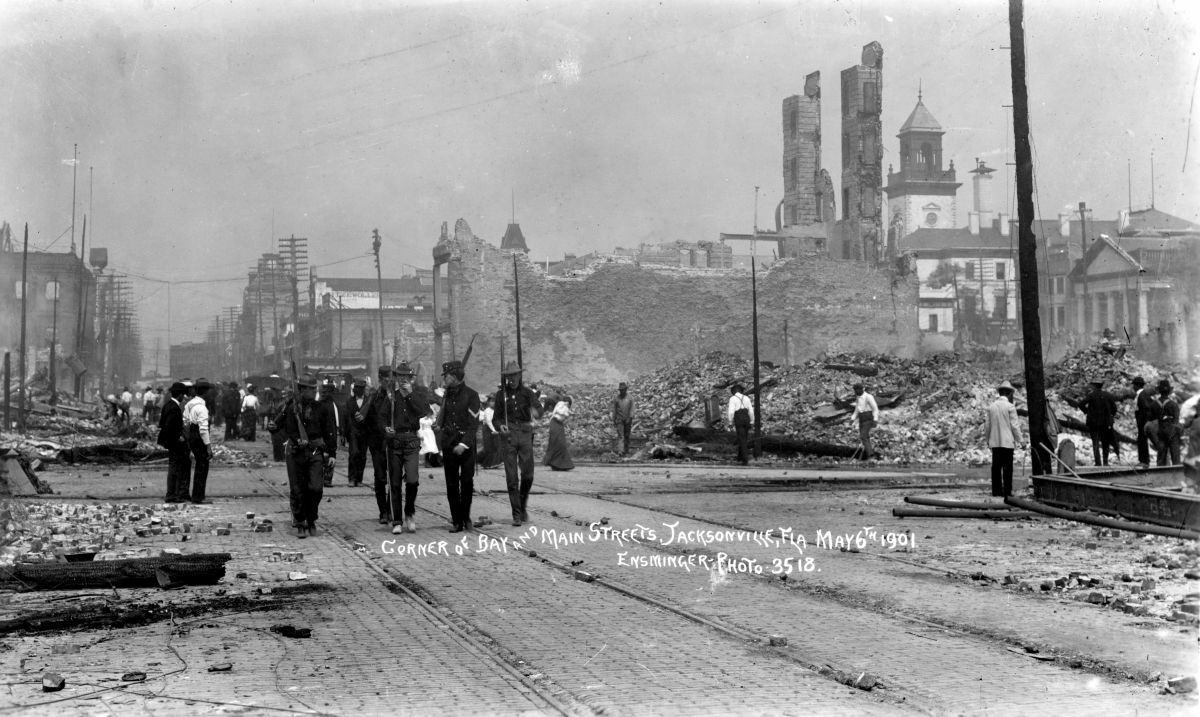

On May 3, 1901, a small fire began at the Cleveland Fiber Factory on the northwest side of downtown Jacksonville. Over the course of roughly eight hours, the fire swept across the urban landscape and damaged or destroyed roughly 130 street-blocks in the city.2 Many of Jacksonville’s houses, shops, mills, factories, churches, hotels, and government buildings were reduced to ash as the fire spread rapidly from west to east through Jacksonville’s downtown. Contemporary estimates of the loss caused by the fire were as high as 15 million dollars.3 The Great Fire of 1901 flattened Jacksonville’s urban core, and what followed was the displacement of thousands of people and the disruption of economic activity. Although only seven people died in the fire, over nine thousand were left homeless.4 The destruction of the fire created an immediate, widespread need for food, clothing, housing, and economic recovery.

In the first week after the fire, the response of state and local government was swift, focused, and effective. The first governmental response to the fire was the proclamation of martial law in Jacksonville by Governor William S. Jennings. On the evening of May 3, State’s Attorney Augustus Hartridge “telegraphed the governor on behalf of a group of ‘prominent citizens’ that martial law be declared,” and the Governor declared martial law in Jacksonville before the sun rose the next day.5 Just hours after the fire, the Governor responded to fears that Jacksonville would quickly become a lawless, chaotic city.

Some citizens criticized Governor Jennings for imposing martial law on Jacksonville because of the strict, authoritative control exercised by the occupying Florida State Troops. However, the presence of troops in the chaotic hours after the fire successfully protected the city, for the most part, from the looting and anarchy that could have followed the fire’s destruction. On May 5, Governor Jennings issued a special order that provided for commissaries, surgeons, law enforcement officials, and housing personnel to be established in Jacksonville to support the occupying soldiers.6 Moreover, the Governor greatly helped the recovery efforts by forming a special relief committee of six members on May 4 and giving the committee $20,000 to spend for the relief effort. While the Governor’s response to the fire impacted both the relief effort and the martial law after the fire, the City Council and City Boards focused primarily on distributing necessary provisions for Jacksonville’s thousands of displaced residents.

On Saturday, May 4, the day after the fire incinerated the core of Jacksonville, government officials began organizing. C. E. Garner, president of the Board of Trade, called the members of the Board to meet at 10:30am that morning, and the Board of Trade formed the Jacksonville Relief Association. Mayor J. E. T. Bowden, who had offered the rooms of his large home to some of the people made homeless by the fire, said on that Saturday morning that the people of Jacksonville should “make the best of a bad situation and work to recover what we have lost without waste of time.”7 Mayor Bowden then called for the City Council, the Board of Bond Trustees, and the Board of Public Works to meet and prepare for emergency response. City Councilman Harry Mason personally donated $250 of his own money to the relief effort and, since he owned a portion of the surviving Everett Hotel, he let the City Council conduct business in some of its rooms.8

The Board of Trade collected a total of $14,000 in donations the day after the fire, which included a $5,000 donation from railroad mogul Henry Flagler.9 The Jacksonville Relief Association created seven committees to address seven specific points of need: the Finance Committee, the Bureau of Information, the Commissary Department, the Bureau of Employment, the Bureau of Lodging, the Bureau of Sanitation, and the Bureau of Transportation.10 The Jacksonville Relief Association quickly began the work of distributing food and clothes to the thousands of homeless Jacksonville residents. The Relief Association had successfully fed two thousand people on May 4, the very day the association was formed.11 Two days later, on May 6, the Relief Association fed 6,500 people. The Relief Association received shipments by rail from suppliers and relief committees as nearby as St. Augustine and as far away as Charleston.12

Not only was food a focus of relief efforts, but housing was a primary concern, too. On May 7, four days after fire, Jacksonville’s homeless residents slept not only in churches and schools in Jacksonville’s unburned suburbs, but they also slept in 200 tents that were sent to Jacksonville by train. Then, on May 8, 2,000 tents were erected in multiple “villages of canvas” throughout the city.13

In addition to the Jacksonville Relief Association, specialty relief associations were created to meet the city’s needs. A Women’s Relief Corps was formed to address the needs of the women left devastated by the fire, and the Corps “did valiant service” to Jacksonville’s homeless women.14 Additionally, at the recommendation of the Board of Trade, the Colored Relief Association was formed to confer with the Jacksonville Relief Association and to consider the relief needs of Jacksonville’s African American community. Because the Board of Trade and the Jacksonville Relief Association were run almost exclusively by White men, the Colored Relief Association was formed to “minister to the specific needs of black citizens” at a time when Jim Crow laws kept Whites and Blacks separate in Jacksonville’s public spaces.15 The formation of the Colored Relief Association reflects not only a focused response to homelessness and hunger in the Black community after the fire, but it also reflects how segregation defined Jacksonville’s institutions during the Jim Crow Era, and even during response to a great disaster.

The swiftness of the relief response allowed Jacksonville to experience an economic rebound and to rebuild after the fire. The food, clothing, and shelter provided by the Jacksonville Relief Association and the other boards and committees made it possible for rebuilding to begin as soon as the heat from the fire was gone. On May 7, businessmen and real estate developers had already begun making plans to rebuild some of the lost buildings, in addition to building entirely new structures in Jacksonville’s urban core.16

Although the responses of the Governor, the City Council, the city boards, and the relief associations required meetings, deliberations, and bureaucratic processes, their responses secured order and fed, clothed, and housed the homeless in the first three days after the fire. The immediate and unpredicted need for food, clothes, and housing further highlights the remarkable speed and effectiveness of the relief response. Author Benjamin Harrison wrote that the relief effort “…was a business system that worked with the monotony of a machine, but with its unfailing regularity… there was to be no more suffering, and Jacksonville walked strongly forward to its appointed future.”17

The relief effort of the members of municipal government boards and associations represents not only focus and determination, but compassion and neighborly spirit. The people who served Jacksonville’s citizens in these bodies began the process of rebuilding Jacksonville from the ground up by tending to the most basic needs of Jacksonville’s suffering citizens. Furthermore, the relief response to the Great Fire of 1901 is arguably the most consequential action taken by Jacksonville’s city government in its history because it managed to resuscitate a city whose social and economic center was demolished. That very resuscitation was essential to the growth of Jacksonville as a major residential and economic center that occurred during the twentieth century. Because of state and local government response, the Bold New City of the South rebounded from one of the most destructive fires in American history.

Carson Welch

Carson is a student at the University of North Florida where he studies history. He plans to go to law school following graduation and hopes to become a civil litigator. Carson is a native of Jacksonville, Florida, and was inspired to study local history by his grandmother, a Jacksonville native, who sparked and fostered Carson’s interest in local history and in Florida history more generally.

Bibliography

Foley, Bill, Wayne W. Wood, Emily R. Lisska, and Carole L. Fader. The Great Fire of 1901. Jacksonville, Fla: The Jacksonville Historical Society, 2001.

Gold, Pleasant Daniel. History of Duval County Including Early History of East Florida. St Augustine, Fla: The Record Company, 1929.

Harrison, Benjamin. Acres of Ashes; the Story of the Great Fire That Swept over the City of Jacksonville, Florida, on the Afternoon of Friday, May 3, 1901. Jacksonville, Florida, J. A. Holloman, 1901.

“Jacksonville Devastated by a Most Destructive Conflagration.” Florida Times-Union and Citizen, May 4, 1901.

“Jacksonville Faces the Emergency and the Relief Work Begins.” Florida Times-Union and Citizen, May 4, 1901.

“Succor for Jacksonville’s Distressed; Loss of Lives as Well as Property.” Florida Times-Union and Citizen, May 5, 1901.

“Systematic Work is Improving Rapidly Conditions in the City.” Florida Times-Union and Citizen, May 7, 1901.

“The Military Rule Perfected; Important Orders Promulgated.” Florida Times-Union and Citizen, May 7, 1901.

“Work is Progressing in Clearing Up Debris; Many Tents Set Up.” The Florida Times-Union, May 8, 1901.