6 The Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens

A History of a City Treasure

Brian A. Little

The Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens is a city treasure for both the citizens of Jacksonville and the tourists. I chose to write about the zoo due to wanting to learn more about the history of the zoo and its purpose. There is a strong possibility that everyone in Jacksonville has heard about the Zoo. However, it has a rich and surprising history. This essay will delve into that history and examine the history of two elephants, animal care, and the benefits zoos provide for wild and endangered animals. The zoo has come a long way since its origins in the Springfield neighborhood in Downtown Jacksonville. For the citizens of Jacksonville, the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens remains a city treasure for all to enjoy.

The history of the of the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens may surprise the residents of Jacksonville. Before the Zoo existed, there were attempts to have an animal display in Jacksonville. In 1888, Jacksonville hosted the Sub-Tropical Exposition with plants and live animals, but the Yellow Fever Epidemic torpedoed the event. Next, Charles D. Fraiser opened an ostrich farm in the 1890s on the Eastside, but he moved it to St. Augustine which became the Alligator Farm in the 1920s. The next attempt at a zoo was Dixieland Park that opened in 1907 and closed in 1908. Eventually, the Zoo, known as the Municipal Zoo, opened on May 12, 1914.1 Jacksonville Park Commissioner Sydney Smith started the zoo at Third and Broad Streets near Hogan Creek with a single animal: a red tail deer. Called the Municipal Zoo, it grew fast with the support of the citizens of Jacksonville.

Superintendent Sydney Smith worked hard in making sure the Municipal Zoo was a success. Shortly after the Zoo opened, Smith took a trip to Atlanta, Georgia. He wanted to “study their park systems, and how to apply it” to the Municipal Zoo along with learning how to provide better housing, better caring, and feeding of the animals.2 Smith also credited the citizens of Jacksonville and the children for their support of the Zoo. The Superintendent stated that the children “are enthusiastic workers who contributed small animals like rabbits and squirrels and contributed pennies and nickels” to help in the “purchase of an elephant or other notable animals.”3 The next superintendent, St. Elmo W. “Chic” Acosta, took on the desire and drive to provide the Zoo with an elephant years later. However, the fast growth of the Zoo created problems for Jacksonville.

First, the Zoo was nearly wiped out in a flood on December 21, 1916, when Hogans Creek overflowed its banks. Second, the nearby residents started to complain about the smell of the animals and their feces. “Chic” Acosta (who succeeded Smith in 1919) and the city leaders knew that the Zoo needed to move to a new location and an 11-acre spot was chosen near the Trout River.4 The city council approved the budget to move the Zoo and to provide monies for the convict labor which cleared out the area for the zoo’s new location. This was convenient since there was a prison farm near the planned location for the new Zoo.5 On July 19, 1925, the renamed Municipal Zoo and Museum of Natural History opened to the public. In 1971, facing dire financial straits, the Zoo formed the Jacksonville Zoological Society, Inc. to oversee business operations. It was successful, which saved the Zoo and started a campaign to improve its infrastructure and animal care. By June 2004, the Zoo took its current name of the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens.

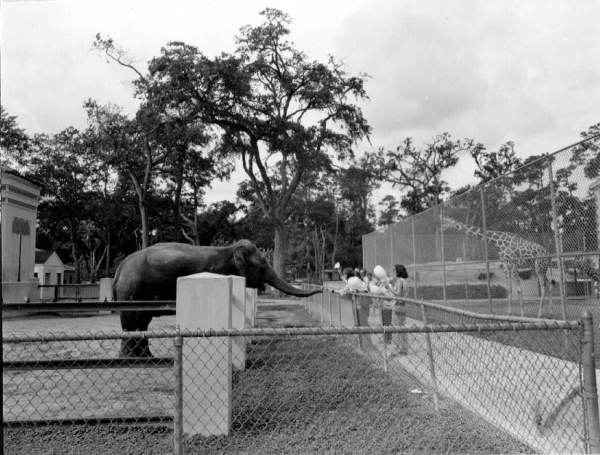

Regarding how animal treatment has changed at the Zoo, an examination of two elephants provided a useful comparison and contrast. The separate cases of Miss Chic and Ali revealed the distinct lives of two elephants. After the Jacksonville Zoo opened at the Trout River on July 19, 1925, Acosta immediately started a fundraising drive to secure an elephant for the Zoo. After raising $3,000 dollars for the Baby Elephant Fund, he purchased a 500 lb. 3-year-old Indian Elephant from a German animal handler, Carl Hagenbeck, of Hagenbeck’s Menagerie in Hamburg.6 The elephant, Miss Chic, was the star at the Zoo upon her debut on July 13, 1926. While she was treated rather humanely during her time, there were some concerning issues. First, she was contained and transported in a small wooden crate from Hamburg to Boston to Jacksonville.7 After her arrival at the Zoo and before her debut, Acosta grew concerned that Miss Chic may become hysterical with the crowds, so he chained “her two hind feet to a post in the middle of her enclosure.”8 Thankfully, there were no incidents of hysteria, and the elephant was friendly and docile with people throughout her time at the Zoo. However, her treatment is unacceptable today. Finally, Miss Chic died of a heart attack at 40-years-old on November 9, 1963. Elephants have a life expectancy of 70-80 years. Miss Chic developed heart problems that were either ignored or the zoo personnel did not recognize her health problems due to a lack of medical knowledge. While her medical treatment could have been better, this is in sharp contrast to the care Ali received in 2024.

Shortly before March 30, 2024, Ali, an African Elephant that had been donated to the Zoo by the singer Michael Jackson in 1997, had surgery to remove his right tusk. Due to the risk of infection of his broken tusk, an international team of veterinary specialists from South Africa to India and the United States (Florida and California) assisted in the complicated and specialized task of dental surgery on a 11,000 lb. elephant.9 Also, the team spent six months crafting the specialized tools and trained Ali not to panic to prepare him for the surgery. This contrasts with chaining Miss Chic in case she had a panic attack. In addition, the veterinarians confronted Ali’s growing health danger of infection before it happened; therefore, the surgeons minimized Ali’s pain. The surgery represented a medical feat of endurance for the Jacksonville Zoo. These specialists from all over the world “worked flawlessly to provide the ivory tower of medicine for Ali.”10

On the lighter side of changes to the health of Jacksonville’s Zoo animals occurred after the summer of 1971. Due to a lack of appropriate cleanliness in the polar bear enclosure, algae started to grow, and it turned the bears’ fur green.11 Contrary to popular belief, polar bear fur is translucent, not white, and it only appears white by reflecting all visible light. No harm befell the polar bears. While the Zoo does not have polar bears now, proper facilities will have to be built to ensure their cleanliness and well-being.

To ensure animal safety and well-being, zoos protect the animals from being fed by visitors. However, this practice was not always in place. For example, in the video A Day at the Zoo, filmed circa 1963, a visiting family fed cotton candy to the elephants.12 This behavior is forbidden to protect the animals. Zoo animals are fed a specialized diet based on the needs of the species. An unfortunate incident happened at the Jacksonville Zoo in the 1970s. A woman visitor brought in a partial loaf of moldy rye bread that contained ergot. Ergot, believed to be responsible for the Salem Witch Trials in February 1692 to May 1693, contains alkaloids that cause vivid hallucinations, violent convulsions, and spontaneous abortions/miscarriages. A pregnant zebra and a Brindled gnu suffered the violent abortions of their young due to ergot poisoning.13 By not allowing visitors to feed the animals, zoos protect the animals and allow visitors to enjoy the animals without harming them.

Finally, zoos continue to promote breeding programs and conservation efforts. However, an opinion writer, Bob Truett, was critical of zoos saving endangered species, and he further argued that too many conservation groups jaded humanity; thereby, weakening the good that conservation groups want to perform on vulnerable animals.14 The evidence gathered by this author disputes his claims about the weakening of conservation groups. Furthermore, one such group, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) argued that they are making a difference in protecting endangered animals, and that zoos are often the last stop before endangered animals become extinct in the wild.15 In the end, zoos, conservation groups, and breeding programs save animals from human depredation and allow people to see and experience animals that they may never get to witness in the wild.

In examining the history of the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, the elephant care of Miss Chic and Ali, animal protection, conservation, and breeding, one issue stands out: zoos are a boon to animals and people. While an animal enclosure cannot compete with the vast wilderness and space of Nature, animals are protected and given the best medical care while living in a zoo. Scientific knowledge about animal biology and behavior has benefitted in the care, feeding, and comfort of wild animals. Finally, zoos provide education for school children and students. Philanthropists provide money, investments, and endowments to improve the environments of zoos. As former Mayor Alvin Brown stated in 2014 on the centennial of the Zoo, he said that the “Zoo contributes to our quality of life” in the city and beyond.16

Brian Little earned his Associate of Arts Degree from Florida State College at Jacksonville and his Bachelor of Arts in History and my Master’s in European History from the University of North Florida. He is primarily interested in German history with a focus on the Nazi/World War II era. He hopes to enter a Ph.D. program and earn his doctorate in German history. As a hard-of-hearing student, he has worked very hard to earn his degrees. He has taken German, French, and Spanish language courses for his studies and enjoyment.

Works Cited

Brown, Alvin (Mayor). “Message from the Mayor.” In Celebrating 100 Years—Jacksonville

Zoo and Gardens, editors Diane David, Alan Rost, Betty Grogan. Jacksonville, Florida: Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, 2014.

Cravey, Beth Reese. “Infected Tusk Leads to Surgery.” The Florida Times Union, March 30, 2024: 1A-2A.

Cruz, Josue A. “Wild Things.” Jacksonville Magazine (August 2018): 32-33.

Graham, Judy. “The Way It Was.” Kitabu IV, no. 1 (January 1975): 11.

Reed, Merlyn B. “Why Can’t We Feed the Animals?” Kitabu IV, no. 21 (April 1979): 1.

Roberts, Pauline G. “What a Great Day for the Zoo…” Kitabu Iv, no. 3 (July 1975): 10.

Roberts, Pauline G. History of the City Zoo. Compiled by Pauline G. Roberts (Scrapbook), Jacksonville, Florida: Self-Published, 1978.

State Archives of Florida (circa 1963.) “A Day at the Zoo.” Florida Memory. Last accessed at April 25, 2024. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/252977

Stepzinski, Teresa. “We Must Find a Way to ‘Co-Exist.’” The Florida Times Union, March 3, 2024: 1A-2A.

Truett, Bob. “Species That Should Be Endangered.” Kitabu IV, no. 16 (May 1978): 1-5.

Truett, Bob. “Endangered Species and Zoos.” Kitabu IV, no. 18 (July 1978): 1-2.

Unknown Author. “New Local Zoo Proves To Be Great Success.” The Florida Times Union, May 28, 1914: 11.

Unknown Author. “Real Interest and Enthusiasm Assure Success of Local Zoo.” The Florida Times Union, June 1, 1914: 5.

Unknown Author. “Supt. Of Parks Plans Big Zoo for This City.” The Florida Times Union, June 29, 1914: 7.

Unknown Author. “May Move City Zoo to Location Out Main Street.” The Florida Times Union, August 15, 1924: 10.

Unknown Author. “City Council Adopts 1925 Budget After Long Session.” The Florida Times Union, October 8, 1924: 7.

Unknown Author. “Green Polar Bear?” Jax Zoo Kitabu 1, no. 1 (Summer 1971): 1

Unknown Author. “Zoos Are Good for Animals…And People.” Kitabu IV, no. 3 (July 1975): 12-13.

Unknown Author. “Your Zoo: The Importance of Breeding Programs.” Kitabu (January/February 1985): 2.

Unknown Author. Celebrating 100 Years—Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, editors Diane David, Alan Rost, Betty Grogan. Jacksonville, Florida: Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, 2014.