2 What’s that Smell?

The Politics and Economics of Odor Control in Jacksonville during the 1980s

Jennifer Cika

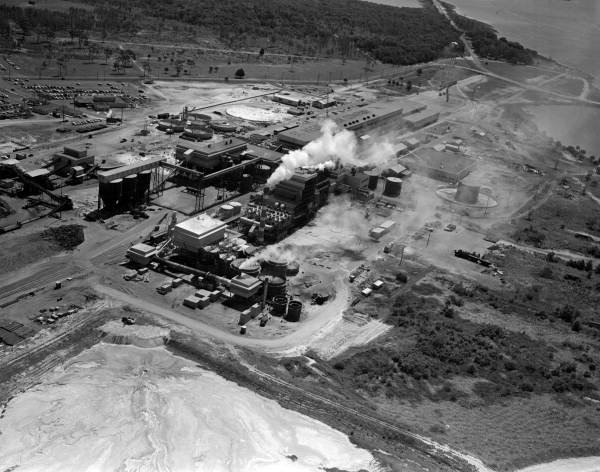

Jacksonville, Florida’s bio-environmental services and division received an unprecedented number of complaints in the 1980s. “What’s that smell?” they asked Evelyn Rogers, a clerk for the air pollution branch of Jacksonville.1 That was just one of many calls that Evelyn and her team were doing their best to handle. Jacksonville had experienced air pollution since the 1940s. The 1940s was the time when Jacksonville began industrializing and creating more businesses for its growing city. The deforestation and the continuous construction of new businesses contributed to the pollution. Because the state government took no action to address the issue, it continued to become a significant problem until 2000. But why did it take so long? All the available scientific evidence linked the cause of pollution to restaurants, paper mills, fertilizer factories, chemical companies, and processing food plants. Despite it being clear about what was happening, local and state government did nothing to close these facilities down. Financial gain of the city and generating more money and profit from businesses would be the only explanation that makes sense for why it took so long for them to make a change and start prioritizing their residents’ lives. In the 1980s, Jacksonville developed a reputation for having an unpleasant odor and prioritizing money over the lives of its residents. This resulted from facilities emitting harmful toxins into the air, causing a stench, and the governments and facilities’ ineffective responses.

The size of Jacksonville’s ecological footprint increased along with the city’s population growth in the years preceding and during the 1980s. The demand for more land increased, which was dangerous given how humans harm the ecosystem to suit their needs. For instance, the construction of paper mills, fertilizer factories, chemical companies, processing food plants, and other businesses that brought in money for a stable economy severely threatened the environment and public health. During the 1980s, deforestation and the development of new companies destroyed biodiversity and released toxic chemicals into the air. Northeast Florida’s toxicity testing from the 1980s documented pollutants emitted by each facility and provided research that indicated whether a business was contributing to air pollution. Although it only shows research on twenty facilities, many more companies released hazardous substances into the air: pentachlorophenol, ammonia, chlorine, and many other chemicals.2

Another contributor to pollution or to Jacksonville’s odor problem was wastewater plants. The largest domestic plant on the St. Johns River was killing fish in laboratory tests. The plant had failed 11 of 17 toxicity tests. The plant receives toxic waste from 100,000 business customers. The toxic wastes from those business emitted sewage like bathroom and kitchen waste, drain water from washing machines, pesticides that seep from lawns, grease from restaurants, wastewater from organic chemical manufactures, oil from waste oil recovery businesses, and inks from printing operations. All these harmful chemicals and wastes entered the plant as sewage and gets dumped into the St. Johns River. Polluted lakes, rivers, ponds, and streams not only affect water quality but also contribute to air pollution.

Facilities and businesses were not the only contributors to Jacksonville’s odor problem and air pollution. Increased commercial development like the creation of new roads, bridges, and highways resulted in more carbon-dioxide emissions from automobiles. For example, traffic on Blanding Boulevard had grown by nearly 4,000 cars per day during the first half of the 1980s. The state Department of Environmental Regulation officials determined that the traffic was in violation of the state air-pollution standards. Scientists expected traffic to release increasing levels of carbon-monoxide into the air.

Exacerbating the traffic problem in the 1980s was Jacksonville’s toll system. The tolls city drivers paid helped the city fund construction of new bridges. Drivers had to stop and pay the toll before crossing some bridges, which led to a back of vehicles waiting in line to cross. Some bridges that had established a toll system were the Mathews, Fuller Warren, and Hart bridges.5

Another contributor to air pollution was littering. People living in rural areas threw their garbage out on their lands while those in more urban areas dumped it in their yards or on roadsides. Many businesses started organized dumping on vacant lots or lands.6 This waste disposal problem along with Jacksonville’s population. Residents’ concerns about the appalling smell in their neighborhood also increased daily. In addition to careless waste disposal, the smell was caused by chemical and paper plants that released hazardous chemicals in air. The city’s apparent neglect of these environmental and air quality issues made city residents increasingly angry.

“The Smell of Money” documentary was created by WJXT-TV in 1985 and highlights how the government and other public officials were failing to address the pollution problem. Duval County’s lung-cancer deaths remained some of the highest in the nation and were linked to acid air pollution.7 The documentary’s name came from the fact that there were no effective actions taken by the city government and other public officials. “The Smell of Money” is a perfect phrase to represent Jacksonville during the 1980s. The government could not care less about what was causing the pollution or harming residents’ health. They were solely interested in the enterprises and factories that would allow them to earn a profit and make money. Addressing the issue would only cause them to lose money and profit. No amount of fulminating against or studying of the problem would eliminate it. Only treatment facilities and anti-air pollution devices would do that task, and both are enormously expensive. The city would have to spend millions of dollars cleaning up rivers and sewage if the pollution issue were to be addressed and fixed. Even Jacksonville’s Electric Authority (JEA) was against the anti-pollution movement. They preferred to continue operating the Northside coal-fired plant without equipment to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions. Don Bayly, chief of Jacksonville’s bioenvironmental services says, “They didn’t volunteer to close the plant down until we talked them into it.”

Other than JEA, there were many other facilities that denied these accusations and made it much harder to solve the issue. Solite, which is a one-thousand-acre clay-mining plant north of Green Cove Springs in Clay County, was accused of emitting hazardous waste for years and polluting the environment. The company began denying these accusations. “There’s a need for what we do here and we’re not polluting anything,” said John Kuiken, senior plant manager and Solite employee for about twenty-five years.9

Jacksonville’s residents’ odor complaints peaked in the late 1980s because of the city government provided little to no effort in fixing the problem. In 1989, there were 4,552 complaints in Jacksonville. Jeanne Oster was one of those who complained. She lived in Arlington in 1989 and expressed wonder about whether the walks she had taken for the past seven years had been doing her more harm than good.10 “The Smell of Money” documentary features an older woman named Mattie Browning. She recounts how everything changed after an oil spill spewed hazardous chemicals into the air. It was so horrible that her neighborhood had to get evacuated. As a result, Mattie had to wear a mask around her house and outside, or even sometimes to sleep. “It makes my life miserable and has worsened my condition” says Mattie.11 Another person featured in the documentary is an older man named Joseph Hagan who explains how every time he steps outside he feels his lungs burn. “It feels acid-like, like there is something burning my lungs” says Hagan.12

Resident complaints continued in Jacksonville into the 1990s. In 1996, Anita James, a community activist who lived in the New Berlin neighborhood near the Dames Point Bridge tried to address harmful emissions coming from the Celotex Corporations gypsum plan that made sheet rock and other building materials.13 Jacksonville’s residents would not have had these health difficulties if the state government and other political officials had sought to address the pollution problem earlier in the city’s history.

During the 1980s, Jacksonville developed a reputation for having an unpleasant odor and prioritizing money over the lives of its residents. Companies like paper mills, fertilizer factories, chemical companies, processing food plants, and other businesses severely threatened the environment and public health. Although there was a large amount of evidence and proof from anti-pollution companies that pointed to the firms responsible for the pollution of air and water, the state government did nothing. The businesses that were fined for causing pollution denied these accusations. The government did not want to act against these companies because they generated revenue and jobs for the city. In addition to all the accusations and proof about the companies spreading pollution and emitting toxic chemicals into the air, there was also a peak in odor complaints during the decade—so many in fact that city and environmental groups could not keep up. These complaints contributed to Jacksonville’s reputation as a foul smelling city that prioritized business over the wellbeing of the people. Hopefully, Jacksonville will not experience anything like this again, and if we do, we will have learned from our mistakes.

Jennifer Cika

Jennifer is a student at the University of North Florida where she is pursuing a Bachelor’s of Business Administration in Management with a minor in Human Resource Management. She aspires to lead and manage her own company. She is interested in corporate laws and maintaining a sustainable organizational culture.

Bibliography

Anderson, Michael. “Fighting Back, Solite Officials: We Don’t Pollute.” Florida Times-Union. December 7, 1994.

Burr, John. “Pollution Fears May Stop Project.” Florida Times-Union. August 14, 1985.

Holland, Nanette. “Weather Complaints: Pollution gripes geared to climate. Florida Times-Union. March 7, 1987.

Crooks, James B. Crooks. Jacksonville: The Consolidation Story, from Civil Rights to the Jaguars. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019.

Keneagy, Beverly. “Nose News Good News on Northside.” Florida Times-Union. September 12, 1992.

Piggott, Jim, and Francine Frazier. “A Look Back: The Toll Jacksonville’s Toll System Had on the City’s History.” WJXT News4JAX, June 8, 2022. https://www.news4jax.com/news/local/2022/06/07/a-look-back-the-toll-jacksonvilles-toll-system-had-on-the-citys-history/.

Rosema, Carrie. Florida Times-Union. February 28th, 1996.

“State Toxicity Tests in Northeast Florida through April 1985.” Florida Times-Union. April 30, 1985

“The Problem Now Is Money, Not Apathy.” Florida Times-Union. June 24, 1989.

WJXT-TV. The Smell of Money. 1985. Television documentary. https://vimeo.com/71583053