65 High Middle Ages

Society and Life

The High Middle Ages saw an expansion of population with rough estimates of the increase from the year 1000 until 1347 indicating that the population of Europe grew from 35 to 80 million. The exact cause or causes of the growth remain unclear; improved agricultural techniques, the decline of slaveholding, a more clement climate and the lack of invasion have all been put forward.

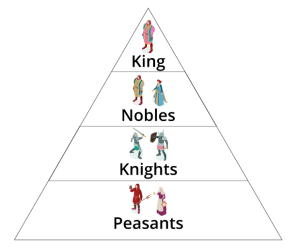

As much as 90 percent of the European population remained rural peasants. Many of them were no longer settled in isolated farms but had gathered into small communities, usually known as manors or villages. These peasants were often subject to noble overlords and owed them rents and other services, in a system known as manorialism. There remained a few free peasants throughout this period and beyond.

European Feudal System

Political States

The High Middle Ages is the formative period in the history of the Western state. Kings in France, England and Spain consolidated their power, and set up lasting governing institutions. Also new kingdoms like Hungary and Poland, after their conversion to Christianity, became Central-European powers. The Papal Monarchy reached its apogee in the early 13th century under the pontificate of Innocent III (pope 1198–1216). Northern Crusades and the advance of Christian kingdoms and military orders into previously pagan regions in the Baltic and Finnic northeast brought the forced assimilation of numerous native peoples into European culture.

During the early High Middle Ages, Germany was ruled by the Saxon dynasty, which struggled to control the powerful dukes ruling over territorial duchies tracing back to the Migration period. In 1024, the ruling dynasty changed to the Salian dynasty, who famously clashed with the papacy under Emperor Henry IV (r. 1084–1105) over church appointments. His successors continued to struggle against the papacy as well as the German nobility.

France under the Capetian dynasty, began to slowly expand its power over the nobility, managing to expand out of the Ile de France to exert control over more of the country as the 11th and 12th centuries. They faced a powerful rival in the Dukes of Normandy, who in 1066 under William the Conqueror (duke 1035–1087), conquered England (r. 1066–1087) and created a cross-channel empire that would last, in various forms, throughout the rest of the Middle Ages. Normans not only expanded into England, but also settled in Sicily and southern Italy, when Robert Guiscard (d. 1085) landed there in 1059 and established a duchy that later became a kingdom. Under the Angevin dynasty of King Henry II (r. 1154–1189) and his son King Richard I, the kings of England ruled over England and large sections of France, brought to the family by Henry II’s marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, heiress to much of southern France.

However, Richard’s younger brother King John (r. 1199–1216) lost Normandy and the rest of the northern French possessions in 1204 to the French king Philip II Augustus. This led to dissension among the English nobility, while John’s financial exactions to pay for his unsuccessful attempts to regain Normandy led in 1215 to Magna Carta, a charter that confirmed the rights and privileges of free men in England. Under Henry III (r. 1216–1272), John’s son, further concessions were made to the nobility, and royal power was diminished. The French monarchy continued to make gains against the nobility during the late 12th and 13th centuries, bringing more territories within the kingdom under their personal rule and centralizing the royal administration. Under King Louis IX, royal prestige rose to new heights as Louis served as a mediator for most of Europe.[2]

Great Religious Movements of the High Middle Ages

Intellectual life

Besides the universities, royal and noble courts saw the development of chivalry and the ethos of courtly love. This culture was expressed in the vernacular languages rather than Latin, and comprised poems, stories, legends and popular songs spread by troubadors, or wandering minstrels. Often the stories were written down in the chansons de geste, or “songs of great deeds”, such as The Song of Roland or The Song of Hildebrand.

Besides these products of chivalry, other writers composed histories, both secular and religious. Geoffrey of Monmouth (d. around 1155) composed his Historia Regum Britanniae, which was a collection of stories and legends about Arthur. Other works were more clearly history, such as Otto von Freising’s (d. 1158) Gesta Friderici Imperatoris detailing the deeds of Emperor Frederick I or William of Malmesbury’s (d. around 1143) Gesta Regum on the kings of England.

Legal studies also advanced during the 12th century. Both secular law and canon law, or ecclesiastical law, were studied in the High Middle Ages. Secular law, or Roman law, was advanced greatly by the discovery of the corpus iuris civilis in the 11th century, and by 1100 Roman law was being taught at Bologna. This led to the recording and standardization of legal codes throughout western Europe. Canon law was also studied, and around 1140 a monk named Gratian (flourished 12th century), a teacher at Bologna, wrote what became the standard text of canon law — the Decretum.

Among the results of the Greek and Islamic influence on this period in European history was the replacement of Roman numerals with the decimal positional number system and the invention of algebra, which allowed more advanced mathematics. Astronomy also advanced, with the translation of Ptolemy’s Almagest from Greek into Latin in the late 12 th century. Medicine was also studied, especially in southern Italy, where Islamic medicine influenced the school at Salerno.[3]

Technology and military

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Europe saw a number of innovations in methods of production and economic growth. Major technological advances included the invention of the windmill, the first mechanical clocks, the first investigations of optics and the creation of crude lenses, the manufacture of distilled spirits and the use of the astrolabe. Glassmaking advanced with the development of a process that allowed the creation of transparent glass in the early 13th century. Transparent glass made possible the science of optics by Roger Bacon (d. 1294), who is credited with the invention of eyeglasses.

A major agricultural innovation was the development of a 3-field rotation system for planting crops. The development of the heavy plow allowed heavier soils to be farmed more efficiently, an advance that was helped along by the spread of the horse collar, which led to the use of draught horses in place of oxen. Horses are faster than oxen and require less pasture, factors which aided the utilization of the 3-field system.

The development of cathedrals and castles advanced building technology, leading to the development of large stone buildings. Ancillary structures included new town halls, houses, bridges, and tithe barns. Shipbuilding also improved, with the use of the rib and plank method rather than the old Roman system of mortice and tenon. Other improvements to ships included the use of lateen sails and the stern-post rudder, both of which increased the speed at which ships could be sailed.

Crossbows, which had been known in Late Antiquity, increased in use, partly because of the increase in siege warfare in the 10th and 11th centuries. Military affairs saw an increase in the use of infantry with specialized roles during this period. Besides the still dominant heavy cavalry, armies often included both mounted and infantry crossbowmen, as well as sappers and engineers. The increasing use of crossbows during the 12th and 13th centuries led to the use of closed-face helmets, heavy body armor, as well as horse armor. Gunpowder was known in Europe by the mid-13th century with a recorded use in European warfare by the English against the Scots in 1304, although it was merely used as an explosive and not as a weapon. Cannon were being used for sieges in the 1320s, and hand held guns were known and in use by the 1360s.[4]

- "Middle Ages" by Wikipedia for Schools is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- "Middle Ages" by Wikipedia for Schools is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- "Middle Ages" by Wikipedia for Schools is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- "Middle Ages" by Wikipedia for Schools is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

the highest point in the development of something; a climax or culmination

(in the Roman Catholic Church) the office or tenure of pope or bishop

the territory of a duke or duchess; a dukedom.

the office or authority of the Pope

an instrument formerly used to make astronomical measurements and calculate latitude