71 Justinian

This section is licensed CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

Byzantine history goes from the founding of Constantinople as imperial residence on 11 May 330 CE until Tuesday 29 May 1453 CE, when the Ottoman sultan Memhet II conquered the city. Most times the history of the Empire is divided in three periods.

The first of these, from 330 till 867 CE, saw the creation and survival of a powerful empire. During the reign of Justinian (527–565 CE), a last attempt was made to reunite the whole Roman Empire under one ruler, the one in Constantinople. This plan largely succeeded: the wealthy provinces in Italy and Africa were reconquered, Libya was rejuvenated, and money bought sufficient diplomatic influence in the realms of the Frankish rulers in Gaul and the Visigothic dynasty in Spain. The rediscovered unity was celebrated with the construction of the church of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, in Constantinople. The price for the reunion, however, was high. Justinian had to pay off the Sasanian Persians, and had to deal with firm resistance, for instance in Italy.

Under Justinian, the lawyer Tribonian (500–547 CE) created the famous Corpus Iuris. The Code of Justinian, a compilation of all the imperial laws, was published in 529 CE; soon the Institutions (a handbook) and the Digests (fifty books of jurisprudence), were added. The project was completed with some additional laws, the Novellae. The achievement becomes even more impressive when we realize that Tribonian was temporarily relieved of his function during the Nika riots of 532 CE, which in the end weakened the position of patricians and senators in the government, and strengthened the position of the emperor and his wife.[1]

The Early Byzantine Period (527–726 CE) was ushered in with the reign of Emperor Justinian I, also known as Justinian the Great–both for his drive to recapture lost territories across the Mediterranean and for his monumental patronage of art and architecture. Justinian’s commissions exemplify the stylistic treatment characteristic of early Byzantine art. One of his most significant architectural commissions was for the Church of the Hagia Sophia.[2]

The Hagia Sophia

Translated as “Holy Wisdom,” the Hagia Sophia was originally built and dedicated in the fourth century and served as the cathedral, or bishop’s seat, for Constantinople. From its dedication in 360 CE to the Nika Revolt of 532 CE, which proved to be the most violent week of rioting in city’s history, the Hagia Sophia was destroyed twice and rebuilt once, reflecting the symbolic power this religious structure held in its relation not only to Christianity but also to the city of Constantinople.

One of Justinian I’s first building campaigns following the Nika Revolt was to rebuild this cathedral. He turned to scholars Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus to design a revolutionary new church, one that adopted a central plan with extensions to the west and east by half dome apses. The dramatically raised, soaring central dome seems to magically float on light, creating a visually spectacular interior that originally had vibrant mosaic work.

Unfortunately, much of the original mosaic work has been destroyed.

Earthquakes in the sixth and ninth centuries, and the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm beginning around 726 CE, significantly damaged the structure and decoration of the Hagia Sophia. In its conversion to a mosque in 1453, when the Ottoman Empire overtook Constantinople, the religious work experienced more degradation, as mosque workers were known to sell individual mosaic tesserae as good luck charms for those who visited the space.[3]

Iconoclast Controversy

Around 726 CE, a period of iconoclasm brought the majority of Byzantine artistic production to a halt. Literally translated as “image breaking,” iconoclasm involved the destruction or desecration of religious imagery for the sake of preventing idolatry, as illustrated in a ninth-century drawing from the Chudlov Psalter. This moment was spurred by ongoing religious debate regarding the function and appropriateness of religious imagery. Those who argued against the use of images feared that worshipers would became too engrossed in the image itself, worshiping the image as an idol rather than focusing on the religious narrative or figures it represents. This controversial issue came to a head under Emperor Leo III, who prohibited the creation of new religious imagery and called for the removal and destruction of extant imagery. During this period, the only acceptable imagery to be included in church interiors was the cross. Following this iconoclastic outbreak, the Middle Byzantine Period (843–1204 CE) began when Empress Theodora reinstated the practice of venerating icons, thereby ushering in a new generation of artistic and architectural production.

The return of the splendor of Byzantine interior decoration can be seen in the Saint Mark’s Cathedral, Venice. Expanding the footprint of the Hagia Sophia to take on a Greek cross shape, Saint Mark’s Cathedral includes five monumental domes, each replete with golden mosaic work (on which work continued until the seventeenth century). While the imagery is no less lavish than earlier examples, imagery has been simplified (e.g., the removal of many superfluous details) since at this point, artists sought to emphasize the primacy of the religious narrative or figure being portrayed.

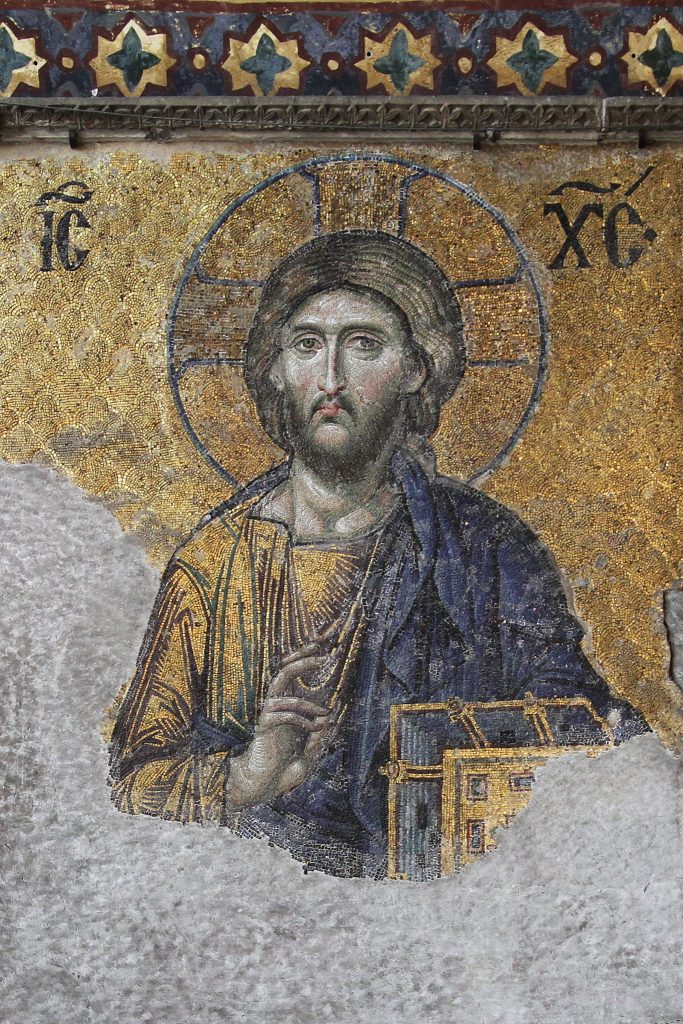

This is illustrated in a relatively contemporaneous version of Christ Pantocrator in the Church of the Dormition, Daphni, Greece (c. 1080–1100 CE). Located in the central dome of the church, this Christ Pantocrator looms large over worshipers. Holding the New Testament in his left arm and assuming a gesture of blessing with his right, Christ here assumes the traditional posture as Pantocrator, or “ruler of all,” a conventional representation of Christ that became popular during this era.[4]

- "Byzantine Empire" from The Lucian of Samosata Project by F. Redmond is published with CC0 ↵

- "Byzantine Art and Architecture" by Alexis Culotta and Amy Raffel is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- "Byzantine Art and Architecture" by Alexis Culotta and Amy Raffel is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- "Byzantine Art and Architecture" by Alexis Culotta and Amy Raffel is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵